A Deep Dive into VideoBERT: Learning Joint Representations with Masked Modeling

VideoBERT, introduced by Google researchers in 2019, was a groundbreaking model that asked a simple yet powerful question: “Can we apply the same self-supervised, ‘fill-in-the-blanks’ magic that made BERT so successful in NLP to the much more complex world of video and language?” The answer was a resounding yes, and it paved the way for a new class of generative vision-language models.

The “Why” - The Quest for a “BERT for Video”

The revolution sparked by BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) was its ability to learn deep contextual understanding of language from raw text alone. It achieved this through a simple but brilliant pre-training task: Masked Language Modeling (MLM). By hiding words in a sentence and forcing the model to predict them from the surrounding context, BERT learned nuanced relationships between words.

VideoBERT’s motivation was to extend this powerful paradigm to the multimodal domain. The goal was not just to find images that match text (like CLIP), but to build a single, unified model that could learn the deep, fine-grained semantic relationship between visual actions and their linguistic descriptions by learning to reconstruct them.

VideoBERT vs. CLIP: A Philosophical Difference It’s crucial to understand the conceptual difference:

- CLIP (Contrastive): Learns by discriminating. Its goal is to tell which text out of many corresponds to a given image. It learns a global similarity score.

- VideoBERT (Generative/Reconstructive): Learns by reconstructing. Its goal is to fill in missing visual or textual information from the available context. It learns a deep, fused, token-level understanding.

The Core Idea - A Unified Vocabulary for Vision and Language

To make a BERT-style model work with video, the authors had to solve a fundamental problem: How do you turn a piece of video into a “word” or a discrete “token” that a Transformer can process just like a text token?

Their solution was Visual Tokenization, a clever process to create a finite dictionary of visual “words.”

- Intuition: Imagine you want to describe every possible human action. You could create a dictionary of “action words” like

walking,running,jumping,eating. VideoBERT does this automatically for visual data. - The Process:

- Feature Extraction: First, the input video is sampled at 20 frames per second. This sequence of frames is then divided into non-overlapping 1.5-second clips (30 frames each). Each of these 1.5-second clips is passed through a pretrained convolutional neural network (ConvNet) called S3D to extract a feature vector. The S3D model, pretrained on the Kinetics dataset(for action classification), is effective at capturing spatio-temporal features related to actions. From the S3D network, they take the feature activations from just before the final classification layer and apply 3D average pooling. This results in a single 1024-dimensional feature vector for each 1.5-second clip.

- Clustering: At this point, each clip is represented by a dense, 1024-dimensional vector. To create discrete “visual words,” the authors use hierarchical k-means clustering on these vectors. They use a hierarchy of 4 levels with 12 clusters at each level. This creates a total vocabulary of $12^4=20736$ unique visual tokens. Each 1.5-second video clip is then assigned the single token corresponding to the cluster centroid it is closest to.

- Creating the Visual Vocabulary: This set of learned centroids is the visual vocabulary. Each centroid acts as a “visual word” representing a common visual concept or action (e.g., one centroid might represent the general concept of “a hand picking something up,” another might represent “a car turning a corner”).

- Tokenization: With this vocabulary, any new video clip can now be “tokenized” by passing it through the S3D feature extractor and then finding the ID of the closest visual word in this vocabulary.

This process turns a continuous, complex video stream into a discrete sequence of visual tokens, making it suitable for a BERT-style architecture.

The VideoBERT Architecture - A Single, Unified Transformer

Unlike the two-tower approach of CLIP, VideoBERT uses a single, unified Transformer encoder to process both modalities simultaneously. This allows for deep, layer-by-layer fusion of information. Of course. The construction of the input sequence for the transformer in VideoBERT is a critical step, as it’s how the model fuses information from two different modalities (language and video) into a single format that the BERT architecture can understand.

The process is detailed in Section 3.2 (The VideoBERT model) of the paper. The core idea is to create a single, combined sequence of discrete tokens, analogous to a pair of sentences in the original BERT model. This input sequence is then converted into a sequence of vectors by summing three distinct embeddings for each token.

Here is a breakdown of how the complete input sequence is constructed for the primary video-text training regime:

1. The Components of the Sequence (The Tokens)

The sequence is built from three types of tokens:

- Linguistic Tokens: These are “WordPieces” derived from the text sentences obtained via Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) on the video’s audio. This is the standard way text is tokenized for BERT.

- Visual Tokens: These are the discrete “visual words” generated from the video stream using the S3D feature extractor followed by hierarchical k-means clustering, as we discussed. Each token represents a 1.5-second video clip.

- Special Tokens: These are crucial for structure and for the model’s training objectives:

[CLS]: A classification token placed at the very beginning of the sequence. Its final hidden state is used to represent the entire sequence for classification tasks, such as predicting if the text and video are temporally aligned.[>]: A special separator token introduced by the authors to explicitly mark the boundary between the linguistic tokens and the visual tokens.[SEP]: Placed at the very end of the combined sequence to mark its termination.[MASK]: Used during training to randomly hide some tokens (both linguistic and visual). The model’s primary task (the “cloze” task) is to predict these masked tokens.

2. Assembling the Token Sequence

The tokens are concatenated in a specific order to form one long sequence. The paper provides a clear example:

[CLS] orange chicken with [MASK] sauce [>] v01 [MASK] v08 v72 [SEP]

Let’s break this example down:

[CLS]: The sequence starts here.orange chicken with [MASK] sauce: The linguistic sentence from ASR, with one word masked for the prediction task.[>]: The special token separating the text from the video.v01 [MASK] v08 v72: The sequence of visual tokens, with one token masked for prediction.[SEP]: The sequence ends here.

3. Creating the Final Input Vectors (The Embeddings)

Just like in the original BERT, the final input vector for each token in the sequence is the sum of three separate embeddings:

- Token Embeddings: Each token (whether it’s a WordPiece, a visual token, or a special token) is mapped to a dense vector from an embedding table. The vocabulary includes all WordPieces, all 20,736 visual tokens, and the special tokens.

- Segment Embeddings: This embedding tells the model which “modality” a token belongs to. For example, all linguistic tokens would get Segment Embedding A, and all visual tokens would get Segment Embedding B. This helps the model differentiate between the two parts of the sequence.

- Positional Embeddings: Since transformers don’t have a built-in sense of order, this embedding is added to give the model information about the position of each token in the overall sequence (e.g., this is the 1st token, this is the 2nd, etc.).

So, for every token in the sequence, its input to the transformer is:

Input Vector = Token Embedding + Segment Embedding + Positional Embedding

This carefully constructed sequence allows the VideoBERT model to learn deep, bidirectional relationships both within each modality (text-to-text and video-to-video) and, crucially, across them (text-to-video).

The Transformer: This single, deep BERT model processes the entire concatenated sequence. The self-attention mechanism allows every token (whether visual or textual) to attend to every other token. This enables the model to learn complex cross-modal relationships, such as how the verb “pour” relates to the visual sequence of a hand tipping a container.

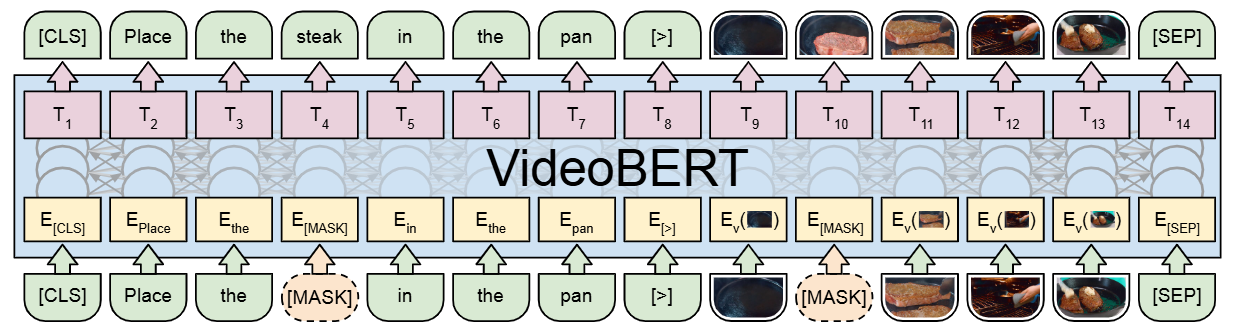

Fig. 1 Illustration of VideoBERT in the context of a video and text masked token prediction, or cloze, task. This task also allows for training with text-only and video-only data, and VideoBERT can furthermore be trained using a linguistic-visual alignment classification objective (not shown here, see text for details).

The Training Process - Learning by “Filling in the Blanks”

VideoBERT is pre-trained on large-scale instructional video datasets from sources like YouTube, using the ASR transcripts as the text modality.

-

Input-Output Training Pair:

- Input: A

(video token sequence, text token sequence)pair. A certain percentage (e.g., 15%) of tokens in both sequences are randomly replaced with a special[MASK]token. - Output: The model’s objective is to predict the original IDs of these masked tokens.

- Input: A

-

The Loss Functions and Mathematics: The total training loss is the sum of two parallel objectives:

1. Masked Language Modeling (MLM) This task teaches the model to understand language in the context of video.

-

Process: A text token $t_i$ from the input caption is randomly selected and replaced with

[MASK]. The entire multimodal sequence is passed through the Transformer. The model must then use the surrounding text and the visual context to predict the original masked word. -

Mathematics: At the output, the vector corresponding to the masked position is fed into a linear layer followed by a softmax function. This produces a probability distribution $p$ over the entire text vocabulary $V_\text{text}$. The loss is the negative log-likelihood, or Cross-Entropy Loss, between this distribution and the true one-hot encoded token $y_i$.

\[\mathcal{L}_{MLM} = -\sum_{i \in M_\text{text}} y_i \log(p(t_i | T_\text{masked}, V))\]where $M_\text{text}$ is the set of masked text indices, $T_\text{masked}$ is the masked text sequence, and $V$ is the video sequence. This loss penalizes the model when it fails to predict the correct word.

2. Masked Visual Modeling (MVM) This is the novel visual equivalent of MLM, teaching the model to understand visual concepts in the context of language.

-

Process: A visual token $v_j$ is randomly selected and replaced with

[MASK]. The model must use the surrounding visual tokens (e.g., the frames before and after) and the entire text caption to predict the original masked visual token. -

Mathematics: The process is identical to MLM, but the prediction is over the visual vocabulary. The output vector at the masked position is passed through a classifier to produce a probability distribution $p$ over all $V_\text{visual}$ cluster centroids. The loss is the Cross-Entropy Loss against the true visual token ID $z_j$.

\[\mathcal{L}_{MVM} = -\sum_{j \in M_\text{video}} z_j \log(p(v_j | V_\text{masked}, T))\]where $M_\text{video}$ is the set of masked visual indices. This loss forces the model to learn, for example, that if the text says “stir the soup,” the masked visual token is likely to be one representing a spoon moving in a bowl.

3. Linguistic-Visual Alignment (LVA) Loss At its core, the alignment task is a binary classification problem. The model is given a pair of a text sequence and a video sequence and must predict one of two labels:

Is_Aligned(Label = 1): The text and video are a correct, temporally aligned pair.Is_Not_Aligned(Label = 0): The text and video are a mismatched pair.

Constructing the Training Data: Positive and Negative Pairs: The model learns to perform this classification task by being trained on a large dataset of both correct and incorrect pairings. This data is generated automatically from the timestamped ASR transcripts and video clips.

Positive Pairs (Aligned - Label 1):

-

A sentence is extracted from the ASR transcript (e.g., “now put the chicken in the oven”).

-

The ASR provides timestamps for this sentence.

-

The sequence of visual tokens corresponding to that exact same time window is extracted from the video.

-

These two sequences—the text and the correctly corresponding video—form a positive pair. The model is taught that for this input, the correct output is

1.

Negative Pairs (Misaligned - Label 0):

-

The same sentence of text is taken (e.g., “now put the chicken in the oven”).

-

However, it is paired with a sequence of visual tokens from a randomly selected, different segment of the video. For instance, the video clip might show someone chopping carrots.

-

This mismatched pair of text and video forms a negative pair. The model is taught that for this input, the correct output is

0.

The Model Architecture for Prediction The model uses the special

[CLS]token to make its prediction. Here’s how the input flows through the transformer to get the alignment prediction:- Combined Input Sequence: The text and video tokens are concatenated into a single input sequence for the transformer:

[CLS] <text_tokens> [>] <video_tokens> [SEP] - Deep Bidirectional Processing: The entire sequence is processed by the multi-layer transformer. Because of the self-attention mechanism, the model can look at all tokens (both text and video) simultaneously to build a rich, contextualized representation for every token.

- The Role of the

[CLS]Token: The[CLS]token is special. By design, its final hidden state (the output vector from the last transformer layer) is used as an aggregate representation of the entire sequence. It is intended to capture the overall meaning and relationship of the text and video combined. - Final Classification: This final

[CLS]vector is fed into a simple, single-layer neural network (a linear classifier) which outputs a probability for theIs_Alignedclass.

-

The Direct Hammer: The Linguistic-Visual Alignment (LVA) Loss

This is the most direct and forceful mechanism. The LVA loss is a binary classification loss that explicitly punishes the model for failing to recognize a mismatch between text and video.

- The Task: For every input, the model must predict if the text and video are a real pair (

1) or a fake, mismatched pair (0). - The Mechanism: The prediction is based on the final vector of the

[CLS]token. For the[CLS]token to become an accurate “reporter” of alignment, the self-attention mechanism inside the transformer must compare the text tokens to the video tokens.- If the model only looks at the text, it has no information about what’s in the video, so it can’t know if they are aligned.

- If it only looks at the video, it doesn’t know what the sentence says.

- How it Forces Alignment: The only way for the model to consistently get the LVA prediction right (and thus lower its LVA loss) is to learn the semantic relationships. It must learn that the text “slice the bread” corresponds to visual tokens of a knife and bread, and that if it sees visual tokens of someone whisking an egg instead, it must output

0. This loss directly forces the model to build a representation in the[CLS]token that captures the result of this cross-modal comparison.

The Indirect Reinforcement: The MLM and MVM Losses

This is the more subtle but equally powerful part of the guarantee. The masked modeling losses create a strong incentive for the model to learn the alignment because the other modality provides powerful clues to solve the prediction task.

Consider this example input:

[CLS] now we will bake the [MASK] in the oven [>] <tokens_for_video_of_a_cake> [SEP]

The model’s task is to predict the masked word.

- Path 1 (Language Only): The model can use the linguistic context. The words “bake,” “the,” and “oven” suggest that the masked word could be “cake,” “pie,” “bread,” etc. This is good, but it’s only a probability distribution.

- Path 2 (Cross-Modal): Through self-attention, the model can also look at the visual tokens on the other side of the

[>]separator. If the visual tokens clearly represent a cake, this provides a massive, unambiguous clue. The model can learn that if it sees those specific visual tokens, the probability of the masked word being “cake” skyrockets.

Why this guarantees alignment:

The model is rewarded (with a lower loss) for making the correct prediction. By learning the alignment between the visual world and the linguistic world, it gets an extra source of information that makes its prediction job for both MLM and MVM much easier and more accurate.

- For MLM loss: Looking at the video helps predict masked words.

- For MVM loss: Looking at the text helps predict masked video segments. (e.g., if the text is “crack an egg,” the model can better predict the visual token for a bowl).

The Unified Result

When you combine these in the total loss

\[\mathcal{L}_{total} = \alpha~\mathcal{L}_{MLM} + \beta~\mathcal{L}_{MVM} + \gamma~\mathcal{L}_{LVA}\]you create a system where:

- The model is punished directly by the LVA loss if it fails to align the two modalities.

- The model is rewarded indirectly by the MLM and MVM losses when it successfully uses the alignment to make better predictions.

The transformer’s shared weights and self-attention mechanism are the engine that drives this. A weight adjustment that helps the model associate the word “pour” with the visual of a liquid for the LVA task is the exact same weight that will then be available to help it predict a masked visual token in the MVM task.

In short, the model is architecturally and mathematically cornered. The path of least resistance to minimizing the total loss is to learn the rich, semantic alignment between text and vision.

Inference - How to Use a Trained VideoBERT

Flexibility of VideoBERT during inference is one of its most powerful features. The pre-trained model acts as a probabilistic “fill-in-the-blank” engine that can be cleverly prompted to perform various tasks, sometimes with no extra training at all.

Here is a summary of the main inference tasks, whether they require extra training, and the exact input format for the VideoBERT model for each one.

1. Zero-Shot Action Classification

This task involves identifying the action in a video clip (e.g., “baking a cake”) without having been trained on a specific action classification dataset.

-

Extra Training Required?: No. This is a “zero-shot” task that uses the pre-trained VideoBERT model directly.

-

Exact Input Construction: The model is given the video and prompted with a text template containing masked slots for a verb and a noun.

- The video clip is converted into a sequence of visual tokens (

v1, v2, ...). - A fixed text template is created:

"now let me show you how to [MASK] the [MASK]." - These are combined into a single sequence for the model.

Input to VideoBERT:

[CLS] v1 v2 v3 ... vN [>] now let me show you how to [MASK] the [MASK] . [SEP] - The video clip is converted into a sequence of visual tokens (

-

How it Works: The model performs a forward pass and predicts the most likely words to fill the

[MASK]tokens. The prediction for the first[MASK]is treated as the action verb, and the prediction for the second is the action object/noun.

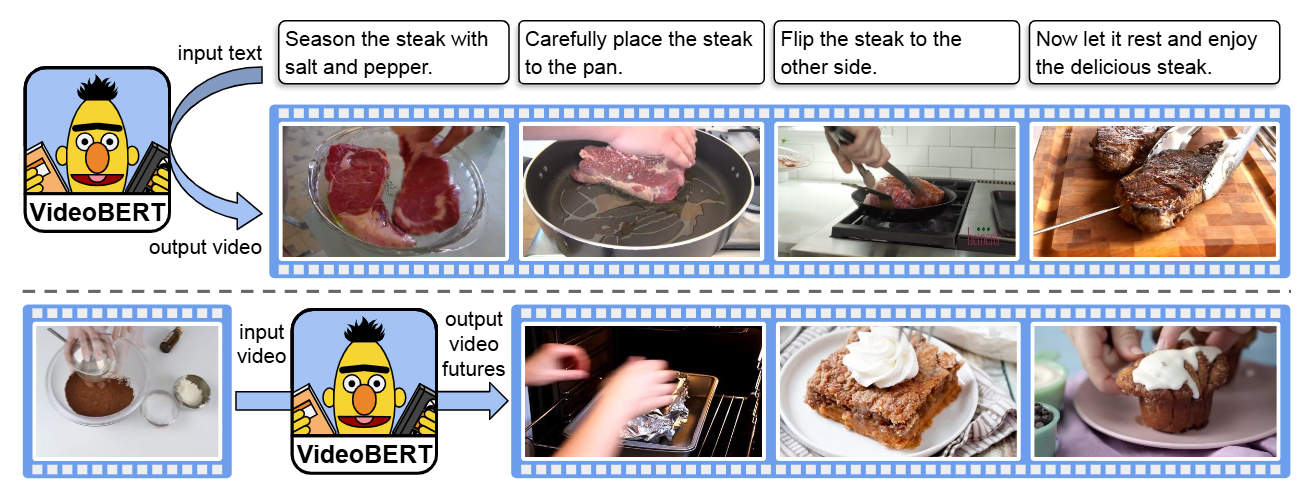

Fig.2 Using VideoBERT to predict nouns and verbs given a video clip. See text for details. The video clip is first converted into video tokens (two are shown here for each example), and then visualized using their centroids.

2. Video Captioning (as a Feature Extractor)

This task involves generating a full sentence describing the content of a video clip. This is the one case where VideoBERT is not used end-to-end.

-

Extra Training Required?: Yes. VideoBERT is used as a powerful, frozen feature extractor. These features are then used to train a separate, smaller, supervised model (like a standard transformer encoder-decoder) on a captioning dataset (e.g., YouCook2).

-

Exact Input Construction (to get the features from VideoBERT): To get a rich feature vector for a video clip, the model is prompted with a generic fill-in-the-blank sentence.

- The video clip is converted into its sequence of visual tokens (

v1, v2, ...). - A fixed text template is used, such as:

"now let's [MASK] the [MASK] to the [MASK], and then [MASK] the [MASK]."

Input to VideoBERT:

[CLS] v1 v2 v3 ... vN [>] now let's [MASK] the [MASK] ... [MASK] . [SEP] - The video clip is converted into its sequence of visual tokens (

-

How it Works: After the forward pass, the model’s internal representations (the output vectors) for the video tokens are extracted. The paper states they average the output vectors of the video tokens and the output vectors of the masked text tokens, and then concatenate them to form a single feature vector. This vector is the final representation of the video, which is then used as the input to the separate captioning model that will be trained.

3. Text-to-Video Generation

This task involves generating a sequence of visual events based on a descriptive input sentence.

-

Extra Training Required?: No. This uses the pre-trained model directly.

-

Exact Input Construction: The model is given the text and asked to fill in the “blanks” for the entire visual sequence.

- The input text sentence is tokenized (

t1, t2, ...). - The visual part of the sequence is filled with a series of

[MASK]tokens, one for each future video clip you want to generate.

Input to VideoBERT:

[CLS] t1 t2 t3 ... tM [>] [MASK] [MASK] [MASK] ... [MASK] [SEP] - The input text sentence is tokenized (

-

How it Works: The model predicts the most probable visual token for each

[MASK]position based on the input text. By taking the top prediction for each slot, you generate a sequence of visual tokens. These can then be visualized by finding the original video frames from the training set that are closest to those token centroids.

4. Future Forecasting (Video-to-Video Prediction)

This task involves predicting what will happen next in a video, given an initial sequence of events.

-

Extra Training Required?: No. This leverages the model’s learned “visual grammar.”

-

Exact Input Construction: The model is given the starting visual tokens and asked to predict the future ones.

- The initial video clip is converted into a sequence of visual tokens (

v1, v2, ...). - The future part of the sequence is filled with

[MASK]tokens. - A generic text prompt can be used, or it can be left empty, but the

[>]separator must be present.

Input to VideoBERT:

[CLS] v1 v2 v3 ... vN [>] [MASK] [MASK] [MASK] ... [MASK] [SEP] - The initial video clip is converted into a sequence of visual tokens (

-

How it Works: The model uses the context of the initial visual tokens to predict the most likely sequence of future visual tokens to fill the

[MASK]slots. As shown in the paper, it can output multiple high-probability futures, reflecting the inherent uncertainty of what might happen next.

Fig. 3 VideoBERT text-to-video generation and future forecasting. (Above) Given some recipe text divided into sentences, $y = y_{1:T}$ , we generate a sequence of video tokens $x = x_{1:T}$ by computing $x^\star_t= \arg \max_k p(x_t = k|y)$ using VideoBERT. (Below) Given a video token, we show the top three future tokens forecasted by VideoBERT at different time scales. In this case, VideoBERT predicts that a bowl of flour and cocoa powder may be baked in an oven, and may become a brownie or cupcake. We visualize video tokens using the images from the training set closest to centroids in feature space.

Code Snippet (Conceptual)

This code illustrates the unique visual tokenizationand input sequence constructionsteps of VideoBERT.

import numpy as np

# --- Assume these are pre-trained/pre-computed ---

class S3DFeatureExtractor:

"""Placeholder for a 3D ConvNet feature extractor."""

def extract(self, video_clip):

# In reality, this would process video frames and return a feature vector

return np.random.randn(512)

class VisualVocabulary:

"""Placeholder for the k-means visual vocabulary."""

def __init__(self, num_clusters=10000, dim=512):

# The centroids are learned offline with k-means

self.centroids = np.random.randn(num_clusters, dim)

def get_token_id(self, feature_vector):

"""Finds the closest cluster centroid (visual word) for a feature vector."""

distances = np.linalg.norm(self.centroids - feature_vector, axis=1)

return np.argmin(distances)

# --- The Core VideoBERT Logic ---

def tokenize_video(video_path, feature_extractor, visual_vocab):

"""Converts a video into a sequence of discrete visual token IDs."""

# 1. Break video into short clips (e.g., 1.5s segments)

video_clips = ["clip1", "clip2", "clip3", "clip4"] # Placeholder for actual clips

visual_token_ids = []

for clip in video_clips:

# 2. Extract a feature vector for each clip

feature_vec = feature_extractor.extract(clip)

# 3. Find the closest visual word ID

token_id = visual_vocab.get_token_id(feature_vec)

visual_token_ids.append(token_id)

return visual_token_ids

def create_input_for_bert(text_tokens, visual_tokens, max_len=256):

"""Constructs the final sequence to be fed into the BERT model."""

# Define special token IDs

CLS_ID = 101

SEP_ID = 102

MASK_ID = 103

# --- Masking for Pre-training ---

# For simplicity, let's mask one text and one visual token

text_mask_position = 2

visual_mask_position = 1

original_text_token = text_tokens[text_mask_position]

original_visual_token = visual_tokens[visual_mask_position]

text_tokens[text_mask_position] = MASK_ID

visual_tokens[visual_mask_position] = MASK_ID

# [CLS] + Text Tokens + [SEP] + Visual Tokens

input_ids = [CLS_ID] + text_tokens + [SEP_ID] + visual_tokens

# Truncate or pad to max_len

input_ids = input_ids[:max_len]

# Also create segment IDs to distinguish text from video

# 0 for text (including CLS and SEP), 1 for video

segment_ids = [0] * (len(text_tokens) + 2) + [1] * len(visual_tokens)

segment_ids = segment_ids[:max_len]

return input_ids, segment_ids, (original_text_token, original_visual_token)

# --- Example Usage ---

if __name__ == "__main__":

# 1. Initialize our components (these would be loaded from pre-trained models)

s3d_extractor = S3DFeatureExtractor()

visual_vocabulary = VisualVocabulary()

# 2. Process a video to get visual tokens

video_file = "path/to/my_video.mp4"

visual_token_sequence = tokenize_video(video_file, s3d_extractor, visual_vocabulary)

print(f"Video converted to Visual Token IDs: {visual_token_sequence}")

# 3. Tokenize the corresponding text (e.g., from ASR)

text_token_sequence = [2054, 2158, 1037, 4440, 2006, 1996, 4248] # "a person is on the beach"

# 4. Create the final masked input for the VideoBERT Transformer

final_input_ids, final_segment_ids, original_tokens = create_input_for_bert(

text_token_sequence.copy(), visual_token_sequence.copy()

)

print(f"\nFinal concatenated and masked input IDs for BERT:\n{final_input_ids}")

print(f"\nCorresponding segment IDs (0=text, 1=video):\n{final_segment_ids}")

print(f"\nGround truth for masked positions: Text ID={original_tokens[0]}, Visual ID={original_tokens[1]}")

Reference

- Official Paper: Sun, C., Myers, A., Vondrick, C., Murphy, K., & Schmid, C. (2019). VideoBERT: A Joint Model for Video and Language Representation Learning. arXiv:1904.01766