A Deep Dive into MERLOT: Learning Temporal and Script Knowledge from Video

MERLOT, which stands for Multimodal Event Representation Learning over Time, is a model from the Allen Institute for AI and the University of Washington. It was designed to address a key weakness in many prior video-language models: their inability to understand long-range temporal structure and causality.

The “Why” - Beyond Short-Term Actions to Long-Term “Scripts”

Many successful video-language models, including VideoBERT and VideoCLIP, are excellent at recognizing and retrieving short, isolated actions (e.g., a 5-second clip of “a person chopping an onion”). However, they often lack a deeper understanding of how these actions fit into a larger sequence of events.

The Limitation: They can identify “chopping an onion,” “sautéing vegetables,” and “adding broth to a pot” as separate events, but they don’t possess the script knowledge to understand that these events typically happen in that specific order as part of a larger script called “making soup.” They lack a commonsense understanding of process and causality over long time horizons.

MERLOT’s Goal: The primary motivation behind MERLOT was to build a model that learns this high-level, long-term script knowledge. The goal was to move beyond simple action recognition and create a model that understands the narrative flow and causal structure of events as they unfold in videos.

The Core Idea - Learning the “Script” through Multimodal Prediction

MERLOT’s core intuition is that one can learn this deep temporal understanding by watching millions of unlabeled YouTube videos and learning to anticipate what happens next. The model is trained to predict missing or future information across multiple modalities (vision, audio, and text) simultaneously.

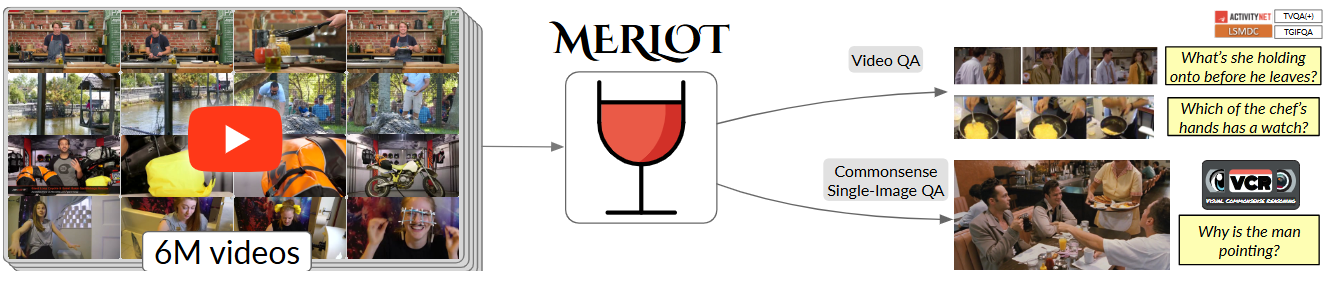

Fig.1 Multimodal Event Representation Learning Over Time. We learn representations of multimodal script knowledge from 6 million YouTube videos. These representations can then be applied to a variety of downstream tasks that require commonsense or temporal visual reasoning.

A Hybrid Learning Approach: To achieve this, MERLOT uniquely combines two powerful self-supervised learning paradigms:

- Reconstructive Learning (Masked Modeling): To learn fine-grained, local, and contextual details, the model is forced to “fill in the blanks” by predicting masked-out video frames, audio segments, and text words.

- Contrastive Learning: To learn high-level, global alignment between a long video segment and its corresponding text description, the model is trained to match correct video-text pairs against incorrect ones.

By training with both objectives, MERLOT learns to be both a skilled detective (reconstructing fine details) and a knowledgeable librarian (matching overall concepts).

The MERLOT Architecture - A Unified Multimodal Transformer

Like VideoBERT, MERLOT uses a single, unified Transformer architecture to jointly process video, audio, and text, allowing for deep, layer-by-layer fusion.

The Basic Unit: Video Segments

The foundation of the input data is the “video segment.” The model processes a sequence of these segments at a time. As described in Section 3.1, each video in the YT-Temporal-180M dataset is split into consecutive segments, where each segment st consists of:

-

Transcribed words ($w_t$): The corresponding speech that occurred during that segment, obtained from YouTube’s Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR).

-

An image frame ($I_t$): A single frame is extracted from the middle of the video segment

Let’s break down the entire input construction process for MERLOT, from the raw data to the final sequence fed into the main transformer.

The process is designed to take video—a medium of images and spoken words over time—and structure it into a format a Transformer can understand. The model processes a sequence of “video segments.” For each segment, it gets a visual part (It) and a textual part (wt).

Fig.2 Left: MERLOT learns to match contextualized captions with their corresponding video frames. Right: the same image encoding is provided, along with (masked) word embeddings, into a joint vision-language Transformer model; it then unmasks ground words (like ‘saw’ in this example) and puts scrambled video frames into the correct order.

The Textual Input ($w_t$)

The textual part is straightforward and follows practices from language models like BERT.

- Source: The starting point is the time-aligned transcript for a video, provided by YouTube’s Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR).

- Segmentation & Tokenization: The transcript is divided into segments, where each segment ($w_t$) corresponds to the words spoken during that slice of time. These words are tokenized using Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) into a sequence of exactly 32 BPE tokens.

- Embedding: Each token is converted into a numerical vector using a learned embedding lookup table.

- Special

[CLS]Token: A special[CLS](classification) token is added to the very beginning of this 32-token sequence. The final hidden state corresponding to this token is later used to represent the meaning of the entire text segment for downstream tasks.

So, for each segment, the textual input becomes a sequence of 33 embedding vectors.

The Visual Input ($I_t$) and the Hybrid Image Encoder

The visual part is more complex. The goal is to take a 2D image frame and convert it into a 1D sequence of visual “tokens” that can be concatenated with the text embeddings. This is where the hybrid ResNet/Vision Transformer (ViT) image encoder comes in, as described in Section 3.2. This entire encoder is trained from scratch.

Here is the step-by-step process:

- Input Frame: A single image frame

Itis taken from the middle of the corresponding video segment. - ResNet-50 Feature Extraction: The image is first passed through a modified ResNet-50 backbone. Critically, the final major block of the ResNet (the C5 block) is removed. This results in a grid of high-resolution visual features (a feature map).

- Vision Transformer Head: This feature map from the ResNet is then fed into a 12-layer Vision Transformer. The ViT’s job is to look at all the different parts of the image and learn the relationships between them (e.g., to understand that a “person” is “holding” a “cup”).

- Final Pooling & Output: The output of the ViT is average-pooled to save computational resources. The final result is a grid of visual features with dimensions W/32 x H/32 (where W and H are the input image dimensions). This grid is then “flattened” into a 1D sequence of visual tokens.

Creating the Unified Input Sequence for the Transformer

Now, we have the sequence of text embeddings and the sequence of visual tokens. They are combined to create the final input for the main Joint Vision-Language Transformer Encoder.

- Concatenation: The two sequences are concatenated together. The model’s input becomes a single, long sequence containing the visual tokens followed by the textual tokens.

- Special

[CLS]Tokens: As mentioned, a[CLS]token is prepended to the text sequence. The image encoder also generates[CLS]hidden states (one for global pooling, another for a specific pre-training task), which are effectively prepended to the visual sequence. - Position Embeddings: This is the final and most critical step for temporal reasoning. After concatenation, position embeddings are added to every single token in the unified sequence. As stated in Section 3.2, “The position embeddings differ between different segments, so as to distinguish between images and captions at different timesteps.” This is how the model knows that the visual and textual tokens for segment #1 came before segment #2, and so on.

The final structure fed into the main transformer for a single segment looks conceptually like this:

[CLS_img, V1, V2, ..., Vn, CLS_txt, T1, T2, ..., T32] + Position Embeddings

When processing multiple segments (e.g., 4 segments at a time for pre-training), this entire structure is repeated for each segment, with unique position embeddings that tell the model which segment each token belongs to. This allows the model to reason about events happening across time.

In practice, for pretraining (Section 3.4), the model takes in examples containing 16 video segments. To manage memory, these are fed to the joint encoder in 4 groups, with each group containing 4 segments. The final sequence length for the joint model is 396 tokens.

The paper describes a system of learned positional embeddings, not a fixed mathematical formula like the sine and cosine functions used in the original “Attention Is All You Need” paper.

Learned Embeddings

Instead of using a function to generate position vectors, the model has an embedding matrix (a lookup table) specifically for positions.

- Concept: Imagine a large table where each row corresponds to a position (e.g., position 0, position 1, etc.), and each row is a vector of numbers (e.g., 768 numbers long). When a token is at position

i, the model simply looks up and retrieves thei-th row from this table. - Training: These vectors in the position embedding table are learned during training. They start as random numbers and are updated via backpropagation, just like the word embeddings and the model’s other weights. The model learns the optimal representation for each position to help it perform its tasks.

The paper provides direct evidence for this approach in Section 3.3 (Temporal Reordering), where it mentions creating separate, unique, and learned position embeddings for shuffled frames (e.g., [image_unk_0]). This wouldn’t be possible with a fixed mathematical formula.

MERLOT’s Two-Tier Positional Embedding System

Because MERLOT deals with sequences of video segments, and each segment is itself a sequence of tokens, it needs to encode two types of positional information:

- Intra-Segment Position: The position of a token inside its own segment (e.g., is this the 1st visual token or the 10th textual token?).

- Inter-Segment Position: The temporal position of the entire segment within the video (e.g., is this segment #1, segment #2, etc.?).

The paper states this clearly in Section 3.2:

“The position embeddings differ between different segments, so as to distinguish between images and captions at different timesteps.”

Conceptual Mathematical Formulation

While there isn’t a complex equation, the process can be formulated conceptually as a series of lookups and additions.

Let:

E_tokenbe the initial embedding of a token (either a visual token from the image encoder or a word token from the text embedding table).PosMatrix_intrabe the learned lookup table for positions within a segment.PosMatrix_interbe the learned lookup table for the temporal position of a segment.ibe the position of the token within its segment.tbe the temporal position of the segment itself (e.g.,t=0for the first segment,t=1for the second).

The final input embedding for a token, E_final, which is fed to the transformer, is calculated as:

This additive approach allows the model to receive signals about both the token’s local role within its segment and the segment’s global role in the temporal sequence of the video, all before the main Transformer even begins its processing.

Based on the detailed descriptions in the paper, here is the breakdown of the number of tokens per segment for both the visual and textual parts during the pre-training phase.

Text Tokens per Segment

The paper is very explicit about the number of text tokens.

- As stated in Section 3.1 (“YT-Temporal-180M”), each video transcript is split into segments, and each segment contains exactly 32 BPE (Byte-Pair Encoding) tokens.

- Furthermore, Section 3.2 (“Joint Vision-Language Encoder”) mentions, “The tokens

wtin each segment begin with a[CLS]token”.

So, for the textual part, each segment consists of:

- 33 tokens in total (32 BPE tokens + 1

[CLS]token).

Visual Tokens per Segment

The number of visual tokens is determined by the output of the hybrid image encoder, which depends on the input image size.

- According to Section 3.2 (“Image encoder”), the model was pre-trained on widescreen images of size 192x352 pixels.

- The same section summarizes the encoder’s output: “given an image of size W × H, the image encoder will output a W/32 × H/32 feature map”.

Using this formula with the pre-training image size, we can calculate the number of visual tokens:

- Width tokens: 192 / 32 = 6

- Height tokens: 352 / 32 = 11

The total number of visual tokens per segment is the product of these dimensions:

- 66 tokens in total (a 6x11 grid of visual features).

For each segment fed into the joint vision-language transformer during pre-training, the breakdown is:

- Text Tokens: 33 (32 for the words + 1

[CLS]token) - Visual Tokens: 66 (from the 6x11 output grid of the image encoder)

This gives a total of 99 tokens per segment.

The paper validates this in Section 3.4, where it states that to save memory, it processes 4 segments at a time, making the joint model’s total input sequence length 396 tokens (99 tokens/segment * 4 segments = 396).

The Training Process - A Hybrid of Masking and Matching

The pre-training process is the core of how MERLOT learns to understand events, and it’s based on a combination of three distinct self-supervised tasks that are trained simultaneously. The model never sees human-created labels; it learns by trying to solve these tasks using the video data itself.

The overall training process involves feeding the model sequences of 16 video segments (each with a frame and 32 text tokens) and calculating a combined loss from the three tasks below. This loss is then used to update all the model’s parameters.

Task 1: Contrastive Frame-Transcript Matching

- Goal: To teach the image encoder to produce meaningful visual representations. The model must learn to associate a video frame with the text that was spoken at the same time. For each inpur pair we have two

ClStoken one for the image segment and one for the text segment. These two embeddings are passed through a shared projection head and then normalized and used for the infoNCE (contrastive) loss. - Input-Output Pair:

- Input: A batch of video frames (

It) and their corresponding text segments (wt). - “Positive” Pair: The correct (

It,wt) pair. - “Negative” Pairs: All other combinations of frames and text within the batch (e.g.,

Itpaired with $w_j$ where $j \neq t$). - Output: A similarity score for every possible frame-text pair in the batch. The model should output a high score for the positive pair and low scores for all negative pairs.

- Input: A batch of video frames (

- Loss Function: A contrastive loss (specifically, a pairwise cross-entropy loss). The image and text representations are projected into a shared embedding space. The model then calculates the dot product between every image and text representation. The loss function pushes the similarity score of the correct (positive) pair to be high, while pushing the scores of all incorrect (negative) pairs to be low. This is conceptually similar to the loss used by CLIP.

Task 2: (Attention) Masked Language Modeling (MLM)

- Goal: To learn a rich, contextualized representation by forcing the model to use both visual and textual context to fill in missing words. Crucially, MERLOT’s “Attention Masking” makes this task more visually grounded.

- Input-Output Pair:

- Input: The full sequence of visual and textual tokens, but with ~20% of the text tokens randomly replaced by a

[MASK]token. - The Twist (Attention Masking): Instead of masking completely random words, MERLOT gives a 50% chance to masking words that are “highly attended-to” by the language-only part of the model. These are often concrete, visual nouns (like ‘saw’ in Figure 2), which are hard to guess from text alone, forcing the model to look at the image.

- Output: A prediction of the original BPE token for each

[MASK]position.

- Input: The full sequence of visual and textual tokens, but with ~20% of the text tokens randomly replaced by a

- Loss Function: A standard cross-entropy loss. It measures the difference between the model’s predicted probability distribution over the vocabulary and the actual ground-truth word.

Task 3: Temporal Reordering

- Goal: The goal of the temporal reordering loss is to directly teach the model the concept of time and causality. It forces the model to learn the logical flow of events, a skill that is fundamental to commonsense reasoning. A human knows that you pick up ingredients before you start cooking, and you open a door before you walk through it. This loss function is designed to teach MERLOT this same kind of temporal intuition.

How It Works: The Step-by-Step Process Here’s the process as described in Section 3.3 (“Temporal Reordering”):

-

Step 1: Get a Sequence of Frames

The model takes in a sequence of

Nvideo segments. For simplicity, let’s say we have 4 frames in their correct temporal order:Frame 1

→Frame 2→Frame 3→Frame 4` -

Step 2: Scramble a Subset of the Frames

A random number of these frames (

iframes, where2 <= i <= N) are chosen and their temporal order is shuffled. Let’s sayFrame 2andFrame 4are chosen and shuffled. The new sequence of frames the model sees might be:Frame 1→Frame 4→Frame 3→Frame 2 -

Step 3: The Crucial “Anti-Cheating” Trick

This is the most important part. You might ask, “Can’t the model just look at the original position embeddings to know the real order?” The authors prevent this with a clever trick:

For the frames that were shuffled (

Frame 2andFrame 4), their original position embeddings are replaced with special, new, learned position embeddings (e.g.,[image_unk_0],[image_unk_1]).This effectively strips the shuffled frames of their original identity, forcing the model to rely on their visual content to figure out where they belong in the timeline.

Meanwhile, the corresponding text captions are always provided to the model in the correct, unshuffled order. This gives the model a ground-truth “storyline” to anchor its reasoning.

-

Step 4: The Prediction Task

Now, the model has to act like a detective. For any pair of the shuffled frames (in our case, the pair is

Frame 2andFrame 4), the model must predict their correct relative order.The model processes the entire scrambled sequence (both visual and textual parts).

It then takes the final hidden state vectors (from the

[CLS]token position) forFrame 2andFrame 4.These two vectors are concatenated together and passed into a small, simple classifier (a two-layer MLP).

This classifier must output a prediction: “Does

Frame 2come beforeFrame 4?” (Yes/No). -

Step 5: The Loss Calculation

The loss is a simple cross-entropy loss.

The ground truth is

t_2 < t_4(since Frame 2 originally came before Frame 4).If the model correctly predicts this order, the loss is low.

If the model incorrectly predicts that

t_4 < t_2, it receives a high loss, and its weights are updated to correct this mistake in the future.

A Simple Analogy

Imagine you are given three comic book panels with the captions removed, and they are out of order:

- A panel of Superman flying away.

- A panel of Clark Kent entering a phone booth.

- A panel of Superman bursting out of the phone booth.

You, as a human, can use your commonsense to reorder them correctly: 2 → 3 → 1. The temporal reordering loss teaches MERLOT this exact skill. It must look at the content of the frames (a man entering a booth, a superhero leaving it) to understand their logical sequence, because its “easy” clues (the original position embeddings) have been taken away.

Combining the Losses

These three losses are not calculated in isolation. During pre-training, they are combined into a single total loss function for each batch. As mentioned in Section 3.4, the contrastive loss is multiplied by a coefficient of 0.25 to balance its gradient contribution relative to the MLM loss.

\[\mathcal{L}_{total} = \lambda_1~L_{infoNCE} + \lambda_2~L_{MLM} + \lambda_3~L_{Reordering}\]This combined loss is what is used to update all the weights in the entire MERLOT model via backpropagation.

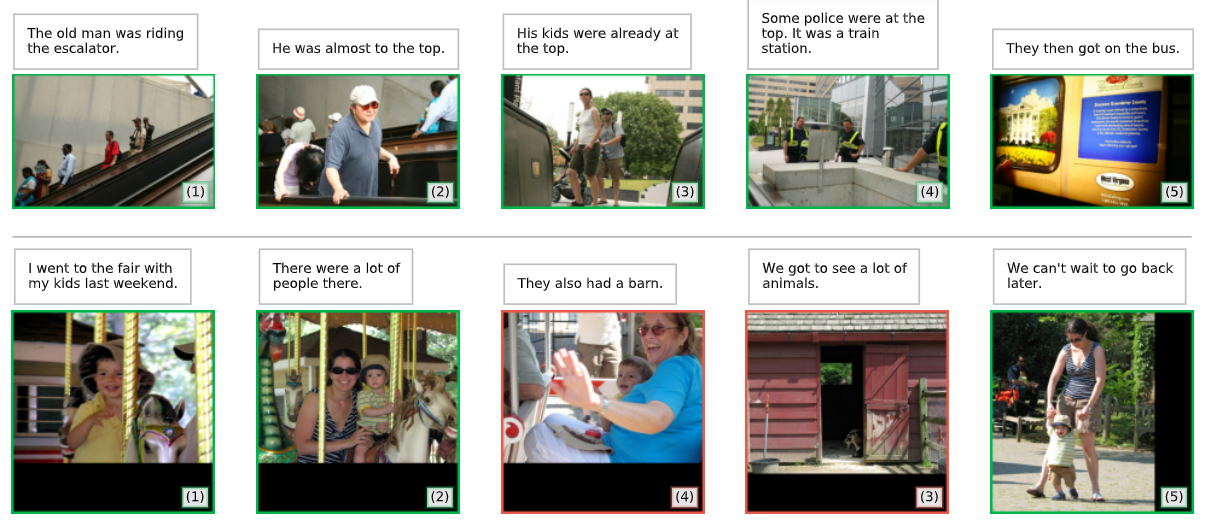

Fig. 3 Zero-shot story ordering (same setup as Table 2). MERLOT performs temporal commonsense reasoning across frames. In the first row, it uses ‘the old man’ mentioned to identify the ‘kids’ as parent-aged; in the second, it identifies riding a merry-go-round as an activity that takes a while.

Inference - Putting Script Knowledge to the Test

The pre-trained MERLOT model, with its deep understanding of temporal progression, excels at tasks that require reasoning about sequences of events.

-

Use Case: Event Sequencing

- Scenario: An application is given five shuffled video clips showing the steps to tie a shoe: 1) crossing the laces, 2) making a loop, 3) wrapping the other lace, 4) pulling the knot tight, 5) showing the final bow.

- How MERLOT Helps: The model can take all 120 possible permutations of these five clips, and for each permutation, calculate the joint likelihood (probability) of that sequence occurring. Because it has learned the “script” for tying a shoe, it will assign the highest probability to the correct chronological order.

-

Use Case: Event Localization from Text

- Scenario: A user wants to find the exact moment in a 20-minute video about car maintenance where the mechanic says, “now, carefully replace the oil filter.”

- How MERLOT Helps: The system can use a sliding window approach. It processes the video in overlapping 30-second clips. For each clip, it calculates the video-text contrastive score against the user’s text query. The clip with the highest similarity score is the one that contains the requested event.

-

Use Case: Future Event Prediction

- Scenario: Given a video showing a person placing a kettle of water on a stove and turning the burner on. What is likely to happen next?

- How MERLOT Helps: The model can be prompted with the video and a masked text prompt like, “The water in the kettle will soon

[MASK].” By predicting the distribution for the[MASK]token, it would assign a high probability to words like “boil” or “heat up,” demonstrating its understanding of cause and effect.

MERLOT’s Contribution and Significance

- Learning Long-Range Temporal Structure: MERLOT’s primary contribution was to demonstrate a successful method for pre-training a model to understand long-term event dependencies and “script knowledge,” going far beyond the short-term action recognition of previous models.

- Hybrid Pre-training: It was a pioneering example of combining reconstructive (masked modeling) and discriminative (contrastive) objectives within a single, unified Transformer. This hybrid approach allows the model to learn both rich, local, fine-grained details and a robust, global understanding of multimodal alignment.

- Advancing Commonsense Reasoning: By learning from the natural progression of events in millions of videos, MERLOT was a significant step toward building models that have a commonsense understanding of how the world works—what actions follow others, what events cause others, and what a complete process looks like from start to finish.

Code Snippet (Conceptual)

This code illustrates the conceptual data preparation for a model like MERLOT, showing how different modalities from a long video are sampled to create a single input sequence.

import numpy as np

# --- Placeholder for pre-trained feature extractors ---

class VideoFeatureExtractor:

def extract(self, frames):

# In reality, a ViT model processing images

return np.random.randn(len(frames), 768)

class AudioFeatureExtractor:

def extract(self, audio_chunks):

# In reality, a VGGish model processing spectrograms

return np.random.randn(len(audio_chunks), 128)

def text_tokenizer(text_list):

# In reality, a WordPiece/BPE tokenizer

return [np.random.randint(0, 30000, size=10) for _ in text_list]

# --- Core MERLOT Data Sampling Logic ---

def sample_multimodal_data_for_merlot(long_video, transcript, num_segments=8, segment_duration=4):

"""

Samples frames, audio, and text from a long video to create

a training instance for MERLOT.

"""

total_duration = len(long_video) # Assume length in seconds

# --- 1. Sample segments across the long video ---

segment_start_times = np.linspace(0, total_duration - segment_duration, num_segments)

video_frames_to_process = []

audio_chunks_to_process = []

text_chunks_to_process = []

print(f"Processing video in {num_segments} segments...")

for start_time in segment_start_times:

end_time = start_time + segment_duration

# Get video frames for this segment (e.g., 2 frames per segment)

frame1 = long_video.get_frame_at(start_time + 1)

frame2 = long_video.get_frame_at(start_time + 3)

video_frames_to_process.extend([frame1, frame2])

# Get corresponding audio

audio_chunk = long_video.get_audio_between(start_time, end_time)

audio_chunks_to_process.append(audio_chunk)

# Get corresponding text from transcript

text_chunk = transcript.get_text_between(start_time, end_time)

text_chunks_to_process.append(text_chunk)

# --- 2. Extract features/tokenize ---

video_features = VideoFeatureExtractor().extract(video_frames_to_process)

audio_features = AudioFeatureExtractor().extract(audio_chunks_to_process)

text_tokens = text_tokenizer(text_chunks_to_process)

# The output would be these three sets of features/tokens, ready to be

# concatenated, masked, and fed into the unified Transformer.

print(f"Extracted {video_features.shape[0]} video feature vectors.")

print(f"Extracted {audio_features.shape[0]} audio feature vectors.")

print(f"Extracted {len(text_tokens)} sets of text tokens.")

return video_features, audio_features, text_tokens

# --- Example Usage ---

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Create dummy video and transcript objects

class DummyVideo:

def __init__(self, duration=120): self.duration = duration

def get_frame_at(self, t): return f"frame_at_{t}s"

def get_audio_between(self, t1, t2): return f"audio_{t1}-{t2}s"

def __len__(self): return self.duration

class DummyTranscript:

def get_text_between(self, t1, t2): return f"text from {t1} to {t2}"

my_long_video = DummyVideo(duration=120) # A 2-minute video

my_transcript = DummyTranscript()

sample_multimodal_data_for_merlot(my_long_video, my_transcript)

**Reference

- Official Paper: Zellers, R., Lu, X., et al. (2021). MERLOT: Multimodal Neural Script Knowledge Models. arXiv:2106.02636