Visual Instruction Tuning-LLaVA

For years, the fields of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Computer Vision have largely advanced in parallel. On one hand, Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have become incredibly proficient at understanding and following complex textual instructions, acting as general-purpose assistants for a wide range of language tasks. On the other hand, vision models have excelled at specific, predefined tasks such as image classification, object detection, or captioning. However, a critical piece has been missing: a unified model that can act as a general-purpose assistant for both visual and language-based instructions.

Imagine an AI you could show a picture of the inside of your fridge and ask, “What can I make for dinner with these ingredients?” Or an AI that could look at a complex diagram in a scientific paper and explain it in simple terms. This requires a model that doesn’t just see an image or understand text, but seamlessly integrates both to follow instructions grounded in visual content.

The primary challenge in building such a model was the lack of suitable data. Training a model to follow visual instructions requires a massive dataset of image-instruction-response triplets. Manually creating such a dataset would be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

This is the core problem that the paper “Visual Instruction Tuning” brilliantly solves. The authors’ central insight was to leverage the advanced reasoning capabilities of a language-only LLM (GPT-4) to generate a high-quality, large-scale dataset for multimodal instruction following. By feeding textual descriptions of images (like captions and object locations) into GPT-4, they prompted it to create diverse conversations, detailed descriptions, and complex reasoning questions about the visual scene. This generated data was then used to teach a multimodal model, LLaVA, how to follow visual instructions, paving the way for powerful, general-purpose vision-language assistants.

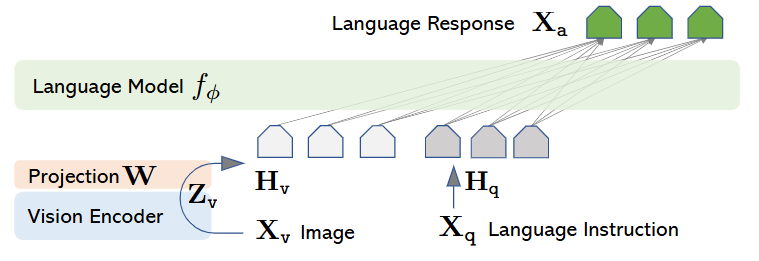

Fig. 1: LLAVA model Structure

The LLaVA Model Architecture

The primary goal of the LLaVA architecture is to effectively combine the capabilities of a pre-trained vision model and a pre-trained language model. The design is simple yet powerful, connecting these two components with a single, lightweight, trainable bridge.

The architecture consists of three main parts:

-

Vision Encoder: This component is responsible for “seeing” the image. LLaVA uses the vision encoder from CLIP (specifically, ViT-L/14), which is already pre-trained on a massive dataset of image-text pairs. When an input image $X_v$ is fed into the vision encoder $g$, it produces a set of feature vectors $Z_v = g(X_v)$. These features represent the rich visual content of the image. The vision encoder’s weights are kept frozen during both stages of LLaVA’s training, preserving its powerful, pre-trained visual understanding capabilities.

-

Large Language Model (LLM): This is the brain of the operation, handling reasoning and language generation. LLaVA uses Vicuna, a high-performing, open-source LLM fine-tuned from LLaMA. The LLM, denoted as $f_\phi$, takes a sequence of text embeddings as input and generates a response.

-

Projection Matrix: This is the crucial link between the vision and language models. The visual features $Z_v$ from the vision encoder and the word embeddings used by the LLM exist in different spaces and have different dimensions. A simple, trainable linear projection matrix, W, is introduced to bridge this gap. This matrix projects the visual features $Z_v$ into the language embedding space, transforming them into a sequence of “visual tokens” $H_v$. \(H_v = W \cdot Z_v\) Each token in $H_v$ has the same dimension as the word embeddings in the LLM, allowing the LLM to process them as if they were part of the text input. You can think of this projection matrix as a translator, converting the “language of vision” into the “language of the LLM.”

The complete data flow for an input image $X_v$ and a language instruction $X_q$ is as follows:

- The image $X_v$ is passed through the frozen CLIP vision encoder $g$ to get visual features $Z_v$.

- The projection matrix $W$ maps these visual features into the language embedding space, producing visual tokens $H_v$.

- The language instruction $X_q$ is tokenized and converted into standard word embeddings, $H_q$.

- The visual tokens and word embeddings are concatenated, forming a unified input sequence $[H_v, H_q]$ that is fed into the LLM, $f_\phi$.

- The LLM then auto-regressively generates the answer tokens, $X_a$.

This architecture is highly efficient because it leverages powerful pre-trained models and only requires training the small projection matrix $W$ and fine-tuning the LLM $f_\phi$.

GPT-Assisted Data Generation

Let’s dive deeper into the mechanics and ingenuity of the GPT-Assisted Data Generation pipeline. This is arguably the most critical contribution of the LLaVA paper, as it solves the primary bottleneck that was holding back progress in general-purpose visual instruction following.

The Fundamental Problem: The Data Bottleneck

Before LLaVA, there was no large-scale dataset of (image, instruction, response) triplets. Existing multimodal datasets were typically simpler:

- Image-Caption Pairs (e.g., from CC3M, LAION): These are great for learning what’s in an image, but they aren’t instructions. A caption like “A dog is catching a frisbee” doesn’t teach a model to answer the question, “What color is the dog?”

- Visual Question Answering (VQA) Datasets: These consist of

(image, question, answer)triplets. While closer, they are often not conversational, lack complex reasoning, and don’t cover the breadth of instructions a general-purpose assistant would need to handle (like “Write a poem about this sunset” or “Explain the humor in this meme”).

Manually creating a massive, diverse, and high-quality dataset to cover all these cases would require millions of dollars and an immense amount of human labor. The LLaVA authors needed a way to create this data scalably and affordably.

The Core Idea: Translating Images into Text for a Language Guru

The key insight is this: GPT-4 is an incredibly powerful reasoning engine, but it is blind. It cannot process pixels. Therefore, to leverage its capabilities, you must first describe the image to it in a language it understands: text.

The process of “retrieving image information” is not about the model seeing the image, but about creating a rich, structured, textual representation of the image’s content and layout. This text then serves as the “visual context” for the text-only GPT-4.

LLaVA uses two types of textual information to represent an image:

- Captions: These provide a high-level, semantic understanding of the entire scene. For an image, there might be several captions describing it from different perspectives. For example:

- “A group of people are packing luggage into a black SUV.”

- “Three people stand around a vehicle in an underground parking garage.”

- “Suitcases and backpacks are on the ground next to a car.”

- Value: Captions give GPT-4 the overall gist of the scene, the main actors, and the general activity.

- Bounding Boxes: These provide precise, localized information about specific objects. Each bounding box is represented as a textual string containing the object’s class name and its spatial coordinates (typically normalized from 0 to 1). For example:

person: [0.681, 0.242, 0.774, 0.694]backpack: [0.384, 0.696, 0.485, 0.914]suitcase: [0.758, 0.413, 0.845, 0.690]- Value: Bounding boxes tell GPT-4 exactly where objects are located. This allows it to answer questions about spatial relationships (“Is the backpack next to the car?”), counts (“How many people are there?”), and object attributes.

By combining captions and bounding boxes, you create a comprehensive textual proxy for the image. The captions provide the narrative, and the bounding boxes provide the specific, grounded facts.

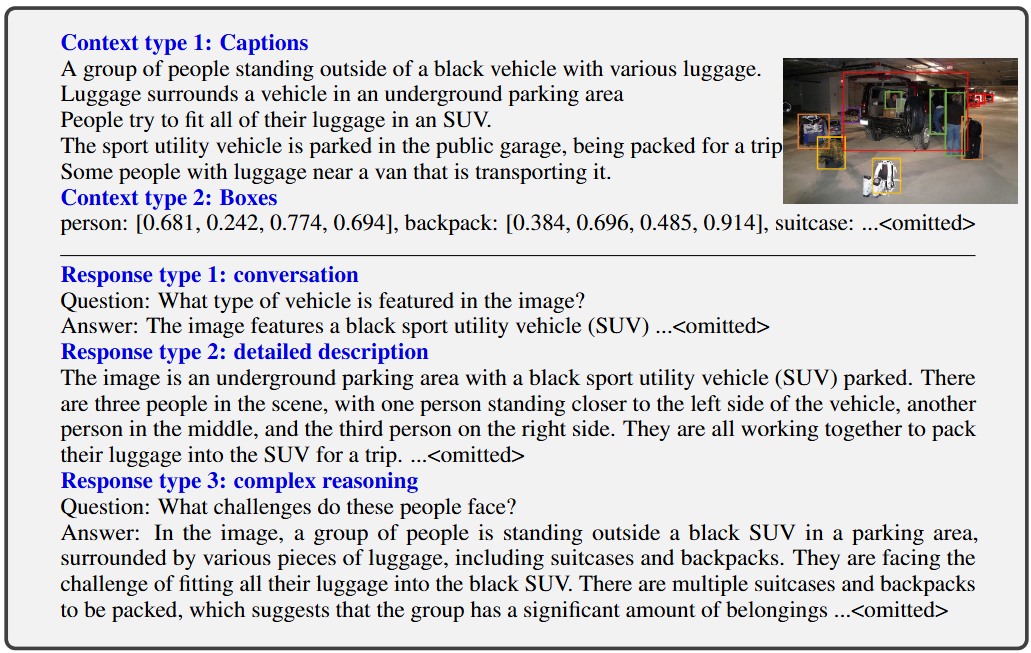

Fig.2 One example to illustrate the instruction-following data. The top block shows the contexts such as captions and boxes used to prompt GPT, and the bottom block shows the three types of responses. Note that the visual image is not used to prompt GPT, we only show it here as a reference.

The Data Generation Pipeline in Detail

The authors used this textual representation to prompt GPT-4 to generate data in three distinct “flavors.” The key technique they employed is called in-context learning or few-shot prompting. Instead of just asking GPT-4 a question, they first provided it with a few high-quality, manually-written examples of the exact type of output they wanted. This steers GPT-4 to produce responses in the correct style, tone, and complexity.

Here is the step-by-step process for generating one data point:

Step 1: Construct the Prompt for GPT-4 A master prompt is created. It starts with a system message to set the persona:

“You are an AI visual assistant. You are seeing a single image described by the following sentences and object locations. Answer all questions as if you are seeing the image.”

Then, a few manually crafted examples (the “few-shots”) are added to the prompt to show GPT-4 the desired format.

Step 2: Provide the “Visual” Context The textual representation of a new image from the COCO dataset is appended to the prompt. This includes:

- The list of captions.

- The list of bounding boxes with their coordinates.

Step 3: Prompt for a Specific Data “Flavor” Finally, GPT-4 is prompted to generate one of the three types of data:

- Conversation: The prompt asks GPT-4 to create a multi-turn dialogue. The goal is to generate questions that are diverse and cover various aspects of the image. The generated conversation might look like this:

- Q: “What type of vehicle is featured in the image?”

- A: “The image features a black sport utility vehicle (SUV).”

- Q: “Where is the vehicle parked?”

- A: “The vehicle is parked in an underground parking area, likely in a public garage.”

- Q: “What are the people in the image doing?”

- A: “The people are trying to fit all of their luggage into the SUV, likely preparing for a trip.”

-

Detailed Description: The prompt asks GPT-4 to synthesize all the provided information (captions and boxes) into a single, comprehensive paragraph. GPT-4’s job is to weave the discrete facts into a coherent narrative, which is a much richer form of data than just the original captions.

- Complex Reasoning: The prompt asks GPT-4 to generate a question that requires logical inference or world knowledge applied to the scene, along with a detailed, step-by-step answer.

- Q: “What challenges do these people face?”

- A: “In the image, a group of people… are facing the challenge of fitting all their luggage into the black SUV. There are multiple suitcases and backpacks to be packed, which suggests that the group has a significant amount of belongings. They might have to strategize and arrange the luggage efficiently… Additionally, they need to consider the comfort of the passengers and visibility while driving…”

Step 4: Collect the Data The generated question-answer pair (or conversation) from GPT-4 becomes a single training sample. This process was repeated for thousands of images from the COCO dataset, ultimately creating the LLaVA-Instruct-158K dataset.

This pipeline is brilliant because it transforms the expensive, manual task of multimodal data creation into an automated, scalable process powered by the reasoning engine of a state-of-the-art LLM. It’s a clever way to “borrow” the intelligence of GPT-4 to teach a new, multimodal model.

The Two-Stage Training Procedure

LLaVA’s training is strategically divided into two stages to ensure both modality alignment and instruction-following capability.

Stage 1: Pre-training for Feature Alignment

The first stage focuses on teaching the model to connect vision and language. The goal is to train the projection matrix $W$ to effectively map visual features from the CLIP encoder into the LLM’s embedding space.

- Dataset: A filtered subset of the CC3M dataset containing 595,000 image-text pairs is used.

- Training Objective: For each image-caption pair, a simple instruction is used, such as “Describe the image briefly.” The model is trained to generate the original caption as the answer.

- Frozen Components: During this stage, both the vision encoder ($g$) and the LLM ($f_\phi$) are frozen. The only trainable parameter is the projection matrix $W$.

- Loss Function: The model is trained using a standard auto-regressive objective. It aims to maximize the probability of predicting the correct next token in the ground-truth caption. The loss is computed only on the tokens of the answer (the caption).

This stage essentially trains a “visual tokenizer” for the frozen LLM. It aligns the visual features with the LLM’s existing word embeddings, so the LLM can understand the visual concepts represented by the projected tokens.

Stage 2: End-to-End Fine-tuning

Once the modalities are aligned, the second stage teaches the model to follow complex instructions.

- Dataset: The 158K instruction-following dataset generated by GPT-4 is used.

- Training Objective: The model is trained on the diverse set of conversations, descriptions, and reasoning tasks from the generated dataset. The input is formatted as a multi-turn conversation.

- Trainable Components: In this stage, the vision encoder ($g$) remains frozen, but both the projection matrix $W$ and the LLM’s weights ($\phi$) are updated.

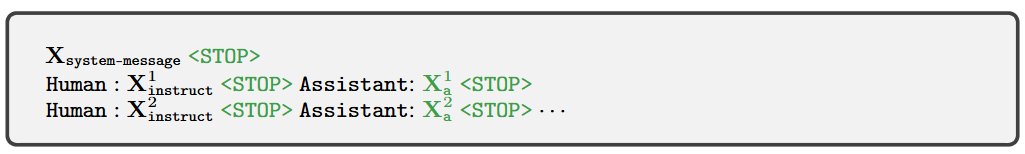

- Loss Function: The loss function is again the auto-regressive objective. The input sequence is structured like this:

Human: <instruction> ASSISTANT: <response>. The model is trained to predict the tokens of the<response>, and the loss is calculated only on these assistant-generated tokens.

This end-to-end fine-tuning allows the LLM to learn how to use the aligned visual information to generate helpful and accurate responses to user instructions.

Mathematical Foundations

Let’s look at the mathematics behind the training process.

Input-Output Training Pairs

A training sample consists of an image $X_v$ and a multi-turn conversation data $(X_q^1, X_a^1, \ldots, X_q^T, X_a^T)$, where $T$ is the total number of turns. We organize them as a sequence, by treating all answers as the assistant’s response; For the $t$-th turn of the conversation, the instruction is $X_{instruct}^t$ and the desired response is $X_a^t$. The instruction is structured as:

\[X_{instruct}^t = \begin{cases} \text{Randomly chose}~ [X_q^1, X_v]~\text{or}~ [X_v, X_q^1],~&\text{the first turn}~\text{for}~ t=1 \\ X_q^t, &\text{The remaining turns}~ \text{for}~t > 1 \end{cases}\]

Fig. 3: The input sequence used to train the model. Only two conversation turns are illustrated here; in practice, the number of turns varies based on the instruction-following data. In our current

implementation, we follow Vicuna to set the system message X_system-message and we set

<STOP> = ###. The model is trained to predict the assistant answers and where to stop, and thus

only green sequence/tokens are used to compute the loss in the auto-regressive model.

Unified Input Sequence and Loss Function

The image $X_v$ and the full instruction sequence $X_{instruct}$ are given to the model. The model’s task is to predict the answer sequence $X_a = x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_L$. The training objective is to maximize the likelihood of the ground-truth answer, conditioned on the image and the instruction. This is formulated as a standard auto-regressive language modeling objective:

\[p(X_a | X_v, X_{instruct}) = \prod_{i=1}^{L} p_{\theta}(x_i | X_v, X_{instruct,<i}, X_{a,<i})\]Here:

- $L$ is the length of the answer sequence.

- $\theta = {W, \phi}$ represents all trainable parameters (the projection matrix and the LLM weights).

- $x_i$ is the $i$-th token in the answer.

- $X_{a,<i}$ represents all the ground-truth answer tokens before the $i$-th position.

In practice, this is optimized by minimizing the negative log-likelihood (cross-entropy loss) over the training dataset. The loss is only computed for the tokens in the assistant’s response, $X_a$.

Attention Mechanism

The paper uses Vicuna, which is a Transformer-based LLM. The core of a Transformer is the self-attention mechanism. In LLaVA, the visual tokens $H_v$ and text tokens $H_q$ are concatenated to form one long sequence. The LLM’s self-attention layers process this entire sequence together. This means that every token, whether visual or textual, can attend to every other token. A word in the instruction can attend to a visual token representing a part of the image, and a visual token can attend to a word in the instruction.

There is no explicit cross-attention module added between the vision and language models. Instead, the alignment and fusion of modalities are handled implicitly by the projection matrix $W$ and the LLM’s own self-attention mechanism operating on the combined sequence. This makes the architecture clean and efficient.

Here is a pseudo-code representation of the training process:

# Stage 1: Pre-training (Feature Alignment)

vision_encoder.freeze()

llm.freeze()

projection_matrix.unfreeze()

for image, caption in pretraining_dataset:

visual_features = vision_encoder(image) # Z_v

visual_tokens = projection_matrix(visual_features) # H_v

# Instruction is a simple, fixed prompt

instruction_tokens = tokenizer("Describe the image briefly.")

# Concatenate visual and instruction tokens

input_tokens = concat(visual_tokens, instruction_tokens)

# Target is the ground-truth caption

target_tokens = tokenizer(caption)

# Generate output and compute loss ONLY on target_tokens

output = llm(input_tokens, labels=target_tokens)

loss = output.loss

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

# Stage 2: Fine-tuning (Instruction Following)

vision_encoder.freeze()

llm.unfreeze()

projection_matrix.unfreeze()

for image, conversation in finetuning_dataset:

visual_features = vision_encoder(image)

visual_tokens = projection_matrix(visual_features)

# Format the conversation history as input

full_prompt = format_conversation(conversation)

instruction_tokens = tokenizer(full_prompt)

# Input includes visual tokens and the full prompt

input_tokens = concat(visual_tokens, instruction_tokens)

# Response is the target

response_tokens = tokenizer(conversation.assistant_response)

# Compute loss ONLY on the assistant's response tokens

output = llm(input_tokens, labels=response_tokens)

loss = output.loss

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

Inference and Fine-tuning on Downstream Tasks

This gets to the heart of how LLaVA is actually used and adapted. Let’s break down the model’s capabilities (tasks), how it can be specialized (fine-tuning), and how it generates an answer for a user (inference).

1. The Tasks: What LLaVA is Built For

At its core, LLaVA is designed to be a general-purpose visual assistant. Its primary “task” is to follow any instruction a user provides in natural language about a given image. Unlike specialized models that only do one thing (e.g., object detection), LLaVA is trained to handle a diverse and open-ended set of tasks.

The visual instruction tuning on the generated dataset gives LLaVA several key capabilities:

- Visual Question Answering (VQA): This is the most straightforward task. The model can answer direct questions about the image content.

- Example: (Given a picture of a beach) “What color is the umbrella?”

- Conversational AI: LLaVA can engage in multi-turn dialogues, maintaining the context of both the image and the prior conversation.

- User: “What is the animal in the photo?”

- LLaVA: “It’s a golden retriever.”

- User: “What is it doing?”

- LLaVA: “It appears to be chasing a red ball on the grass.”

- Detailed Image Description: The model can synthesize the visual information into a rich, coherent paragraph, going beyond simple captioning.

- User: “Describe this scene in detail.”

- LLaVA: “This is a vibrant market scene, likely in Southeast Asia. There are stalls filled with colorful fruits like dragon fruit and mangoes. A woman in a conical hat is arranging her produce, while several customers browse in the background…”

- Complex Visual Reasoning: This is where LLaVA shines. It can infer information that isn’t explicitly visible by combining visual cues with its pre-trained world knowledge from the LLM.

- User: (Given a picture of a messy kitchen with flour everywhere) “What likely just happened here?”

- LLaVA: “It seems like someone was baking and had an accident. The spilled flour and scattered utensils suggest that a bag of flour may have burst or been knocked over during the cooking process.”

- Emergent Abilities: Because LLaVA is built on a powerful LLM, it exhibits capabilities it was never explicitly trained for. The paper highlights several of these:

- Explaining Memes: It can understand the cultural context and humor in a meme by combining the text and the image.

- Optical Character Recognition (OCR): It can often read and understand text within an image.

- Code Generation: Given a hand-drawn sketch of a website, it can generate the corresponding HTML/CSS code.

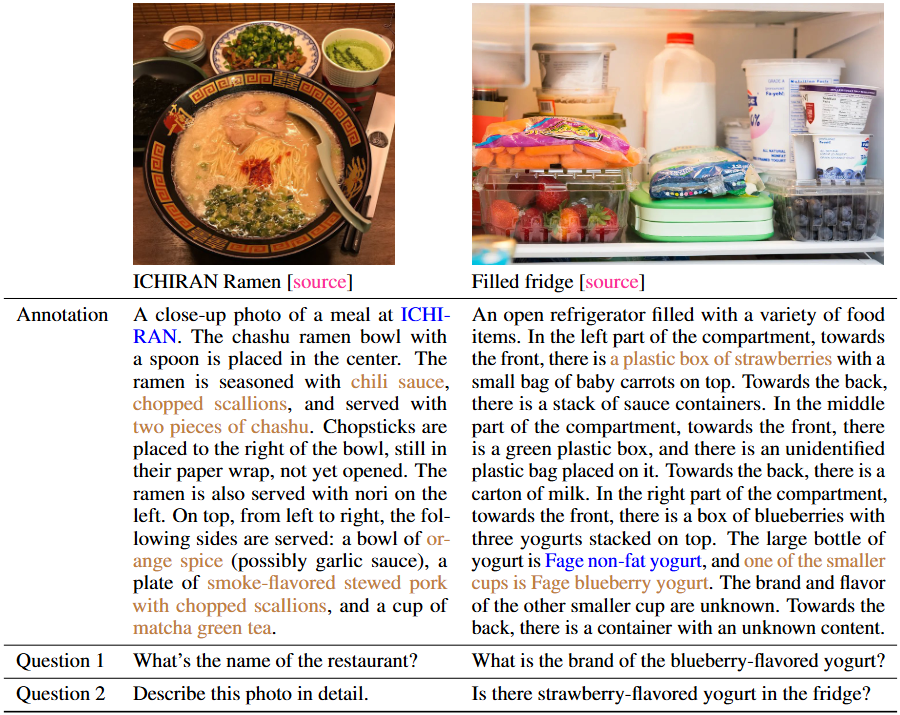

Fig.4 Challenging examples from LLaVA-Bench (In-the-Wild), we provide extremely-detailed annotation for each image for an accurate evaluation. Some questions require the model to extract details from high resolution image and to have a broad knowledge coverage.

2. Fine-tuning: Adapting LLaVA for Specialized Tasks

While LLaVA is a powerful generalist, you might need a specialist for a particular domain (e.g., medical imaging, satellite analysis, etc.). The LLaVA model serves as an excellent foundation model that can be further fine-tuned for these specific tasks.

The process is a continuation of the Stage 2 training, but on a new, specialized dataset. The paper demonstrates this with the ScienceQA benchmark.

The Fine-tuning Process (using ScienceQA as an example):

-

Identify the Target Task: The goal is to answer multimodal science questions that may include images, text, or both.

- Format the New Dataset: This is the most critical step. The new dataset must be converted into the

(instruction, response)format that LLaVA was trained on.- The ScienceQA Data: A sample might have a question, a block of context text, and an image. The correct output includes a detailed reasoning process (a “chain of thought”) and the final multiple-choice answer.

- Formatting for LLaVA:

- Instruction (

Xinstruct): Concatenate the context text, the question, and the image (as visual tokens). This becomes the user’s prompt. - Response (

Xa): Concatenate the reasoning text and the final answer. This becomes the target for the assistant’s response.

- Instruction (

- Execute the Fine-tuning:

- Start with the base LLaVA model that has already completed both stages of its initial training.

- Train the model on the newly formatted ScienceQA dataset.

- As in Stage 2, the vision encoder remains frozen, while the projection matrix (W) and the LLM’s weights ($\phi$) are updated.

- The model learns to apply its general reasoning skills to the specific domain of science questions, improving its performance significantly.

This fine-tuning paradigm is extremely powerful. It means you don’t have to train a model from scratch for every new task. You can leverage the vast knowledge in LLaVA and simply adapt it, saving enormous amounts of time and computational resources.

3. Inference: How LLaVA Generates an Answer

Inference is the process of using the fully trained model to get a response for a new, unseen image and question. It is a step-by-step generative process.

Step 1: User Input The user provides an image and a text prompt (the instruction or question).

Step 2: Visual and Text Processing

- The image is passed through the frozen vision encoder and the trained projection matrix. This produces a fixed sequence of “visual tokens” ($H_v$).

- The text prompt is passed through the tokenizer, creating a sequence of standard text tokens ($H_q$).

Step 3: Sequence Combination The visual tokens and text tokens are concatenated into a single sequence. This forms the initial context that is fed into the LLM. $\text{Input_Context} = [H_v, H_q]$

Step 4: Auto-regressive Generation This is where the magic happens. The LLM generates the answer one token at a time in a loop:

- Prediction: The LLM takes the

Input_Contextand computes a probability distribution over its entire vocabulary for what the very next token should be. - Sampling: A token is chosen from this distribution. (This can be done greedily by picking the most likely token, or using more advanced sampling methods).

- Append: The newly chosen token is appended to the

Input_Context. The context now includes the original input plus the first token of the answer. - Repeat: The process loops back to step 1. The model now predicts the second token of the answer based on this new, longer context.

This loop continues, with the model extending its own answer one token at a time, until it generates a special <end-of-sequence> token.

Step 5: Final Output The sequence of generated tokens is decoded from their token IDs back into human-readable text, which is then presented to the user as the final answer.

Limitations

The limitations can be grouped into several key areas:

1. Vision-Related Limitations

These issues stem from the “eyes” of the model, the CLIP Vision Encoder, and how it processes images.

-

Difficulty with High Resolution and Fine Details: The Vision Transformer (ViT) in CLIP processes images by breaking them down into a grid of fixed-size patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels). This means extremely small objects, fine print, or intricate details can be lost or averaged out within a patch. The paper explicitly points this out with its “ramen” example. The model can describe the ramen bowl, but cannot read the name of the restaurant on the sign because the text is too fine-grained. Similarly, in the “fridge” example, it struggles to identify the specific brand of a yogurt container.

-

Imperfect Optical Character Recognition (OCR): While LLaVA shows a surprising emergent ability to read text in images, it was never explicitly trained for OCR. Its performance is therefore unreliable. It can fail on stylized fonts, blurry text, or text at unusual angles. It is not a replacement for a dedicated OCR system.

-

Struggles with Precise Counting and Spatial Relationships: Large language models are notoriously bad at precise counting, and LLaVA inherits this weakness. It might correctly identify that there are “several cars” in an image but fail if asked to count exactly “how many cars” there are, especially if the number is greater than 3 or 4. Similarly, while it can handle simple spatial queries (“Is the cat on the mat?”), Its understanding of complex spatial arrangements can be brittle.

2. Reasoning and Knowledge Limitations

These limitations are inherited from the “brain” of the model,the Vicuna LLM.

-

Visual Hallucination and Compositional Errors: This is one of the most significant limitations. Just as LLMs can “hallucinate” facts in text, LLaVA can hallucinate objects or relationships in images. A classic example from the paper is the strawberry yogurt problem. The image contains strawberries and plain yogurt in separate containers. When asked if there is “strawberry-flavored yogurt,” the model answers “yes.” It correctly identifies the “strawberry” patches and the “yogurt” patches but incorrectly composes them into a single concept that doesn’t exist in the image. This reveals a failure to grasp the holistic scene.

- Lack of Domain-Specific Knowledge: The model’s knowledge is limited to the general information contained in Vicuna’s pre-training data (mostly the web). It will not understand highly specialized content, such as:

- Medical Images: It cannot interpret an X-ray or an MRI scan.

- Technical Schematics: It would fail to understand a complex engineering diagram or an electrical circuit.

- Niche Cultural Context: It might not understand a meme or symbol specific to a small community.

- Brittleness in Logical Reasoning: While capable of impressive reasoning, the model can still make simple logical errors or be easily misled by a cleverly phrased prompt. Its reasoning is probabilistic and associative, not formally logical.

3. Architectural and Data-Induced Limitations

These are deeper issues related to how LLaVA is built and trained.

-

The “Bag of Patches” Problem: This is related to the vision limitations but is more fundamental. Because the ViT first converts the image into a set of patch embeddings, the model can sometimes perceive the image as a “bag of features” rather than a coherent, structured scene. The self-attention mechanism works to overcome this, but it doesn’t always succeed, leading to compositional errors like the strawberry yogurt example.

-

Simplicity of the Projection Layer: LLaVA uses a simple linear projection matrix to connect the vision and language models. This is computationally efficient but may be a bottleneck for information flow. More advanced models that came after LLaVA (like Flamingo or BLIP-2) use more complex mechanisms like cross-attention or dedicated “Q-Former” modules to more intelligently query the visual features and extract the most relevant information for a given text prompt.

-

Limitations of the Generated Data: The model is only as good as its training data.

- Source Bias: The instruction data was generated using images from the COCO dataset, which mostly contains common, everyday objects and scenes. The model is therefore less capable when dealing with abstract art, scientific charts, or other out-of-distribution visual content.

- Quality Ceiling: The quality of the instruction-following data is capped by the ability of GPT-4 to generate it from text-only descriptions. Any nuances lost in the text-to-image translation (e.g., subtle emotional expressions, complex textures) will not be present in the training data.

In conclusion, LLaVA was a seminal work that demonstrated the viability and power of visual instruction tuning. Its limitations, in fine-grained perception, logical consistency, and its architectural simplicity, were not so much failures as they were crucial signposts that highlighted the key challenges for the field to solve next.

Reference

The work described here was introduced in the following paper:

- Title: Visual Instruction Tuning

- Authors: Haotian Liu, Chunyuan Li, Qingyang Wu, and Yong Jae Lee

- Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.08485

- Project Page: https://llava-vl.github.io/